The two main economic transitions of our time – namely digitalization and transition to renewables – require raw materials. No one can imagine the usage of larger supercomputers, automatization or electric cars and wind parks without lithium. However, resources are rare and concentrated in a couple of countries, currently mostly outer EU-territory, which alarmed the EU-commission to secure its access to raw materials through the Critical Raw Material Act (CRMA) – a 94-page long proposal for securing Raw Materials for the EU industry.

But why should citizens even care about one more out of dozens of EU strategies?

As the proposal is just on the way, proposed in March 2023, no one is yet to say what impacts it might have, but it is yet visible that the EU is turning an eye on the Western Balkans as an alternative source for Raw Materials. The Western Balkan countries are at risk of becoming one of the many countries to fuel the EU by giving away its resources, and there is only speculation about under what conditions that might happen. Will local communities in Bosnia and Hercegovina be forced to carry the burden of contamination and environmental pollution for the greening of the EU economy?

The European Critical Raw Materials Act

Energy transition worldwide will lead to extreme spurs of demand of raw materials within the next couple of decades. The EU document lists explicitly the rise in demand of:

- Rare materials for magnets used in wind turbines and electric vehicles (6-7 fold)

- Gallium for semi-conductors (17-fold)

- Lithium (89-fold) (EU Commission 2023a).

Within those transitions, the EU enters the field of worldwide “resource competition”, (EU Commission 2023a, p. 1), which will not only be demanded more strongly from all countries over the world but which are as well concentrated in the hands of a few country resources. Moreover, the war in Ukraine, Chinese protectionist policies and interruptions of global value chains during Covid19 and before have shown that reliability of previous specific sources is not given anymore.

Fluent and automatized production structures as well as fast investments into renewable energy and automation require a stable disposability of materials as the first step of the value chain. However, while the industrial development, production and research institutes are all located in the industrial centers of the EU, the latter, the material sources are mainly coming from outer-EU regions. The EU has been traditionally relying on China, on African suppliers, and Latin American Countries, often still based on former colonial relationship. Those former colonies would nowadays be supplier countries for raw material to meet EU demand. But as the global landscape is changing, the EU sees its industrial development and living standard, though always at the front of the global sphere, threatened through potential material shortages. The wind energy and automotive sector are in particular under higher supply risk (Hedberg 2020). Many raw materials are concentrated in Russia, which is affected by war, and China, which is subject to geopolitical tensions. Other key raw material exporters have been putting up higher export restrictions (e.g. Kazakhstan, India, Argentina) (OECD, 2022). With the CRMA, the EU sets up a consolidated legislative framework to diversify and be less reliant on their former raw material sources – the EU shall be the independent, autonomous economy, which, if at all, should have specific partnerships with countries which rely on EU but not elsewise.

The CRMA entails specific means to secure the EUs preferred access over other countries when it comes to strategic materials, among which the most important strategic partnerships and investments. Strategic partnerships are already put in place, however, the document is explicitly drafted as a response to current events and for a consolidation of actions in a more strategic manner.

While securing exclusive access to their sources becomes the main objective of the Act, promises of circularity and material efficiency on the other side of the value chain are merely mentioned to limit its resource demand through second usage. Environmental considerations are only sparsely mentioned across the document, and detailed elaboration on resource acquaintance is only followed by mere grasps of environmental regulations and waste management promises.

The Act reveals itself more as a tool to protect EU competitiveness: Circumventing the global, more competitive market over resources, by securing exclusive access through strategic investments and partnerships. Limiting global value chain disruption, securing energy and digital investments and production within the EU, independent from regional or global crises, conflicts or other value chain disturbances.

Aims of the Initiative

The Act first establishes a main basis of priority materials which are to mine: Those, which the EU wants to secure exclusively because it sees them critical for their own development, and where the EU is seeking for new mining opportunity within EU and specifically outer. As such, the EU is firstly setting targets for each EU country to upscale their domestic mining as to become less dependent from outer sources. By 2030, 10% of Critical Raw Materials are supposed to stem from domestic sources. For newer EU members and prospective EU members, this also means get prepared for getting more mines from Western European Companies.

To limit dependency from one source country, the EU foresees a cap – maximum import share of one country in strategic raw materials shall not exceed 65%. Strategic Partnerships with “third countries” on raw materials, which are already part of the 2020 EU Raw Material Strategy, help diversifying the supply chain and shifting focus on mining away from Africa to limit Europe´s dependency (Wouters, 2023). Strategic partnerships are already put in place with Ukraine or Canada, and is currently negotiating with Chile over Lithium. What country is eligible as Strategic Partner is determined by 4 categories, of which one are environmental and social standards. However, the formulation is unclear and vague. CSO´s criticize that there is no strict conditionality on specific environmental and social safeguards for Strategic Partnerships (Gonzalez 2023).

As supply chain diversification needs to appear over the next couple of years and demand for CRM is skyrocketing, fast the EU can only satisfy its needs if quickly upscaling EU mining investments into on a much wider range. International investors should be attracted by accelerating the procedure for Strategic Projects. In fact, the document lists the, from their side, most hindering circumstances for projects:

“Sometimes difficult access to funding, lengthy and complex permitting procedures and the lack of public acceptance as well as potential environmental concerns are major impediments to the development of critical raw materials projects.“ (EU Commission 2023a, p.2).

Protection of the environmental and the local population are, though mentioned at several points in the document, not something which should explicitly be addressed and raised, but a disturbing factor like a rocket on the way to profitable and strategic mining investments.

In one of the potential future policy options, Strategic projects would get wider access to permitting support from Member States and funding from a CRM Fund (EU Commission 2023a) and get permission under lighter environmental standards. The timeframe between proposal for a project and implementation is planned to be radically shortened from up to decades to a couple of years only, which would also limit the timeframe for public consultations, protests, scope for change of the project for the local community (Menga, 2023). In fact, permit granting for Strategic Projects is supposed to take 2 years maximum, in some cases a year only. This gives extremely few time for local communities and environmental groups to react, although it is well known that mining projects can cause heavy pollution with large health and environmental impacts and therefore require specific impact assessments (Gonzalez 2023). The time-frame for public consultations and environmental impact assessment however will be limited to 90 days only.

There is a notion of expansion of waste management, where waste sites and some provisions for recycling, though not elaborated on in detailed, should be obligatory. In the end, the EU aims to pursue 15% of its raw materials from recycled sources by 2023 – which again should limit EU demand and make it thus more robust to material shortages (EU Commission 2023a, Menga 2023).

Which resources?

The Act applies specifically to “non-energy, non-agricultural raw materials” – that is, to materials which are classically mined. Classification can occur under two categories:

- Strategic Raw Materials: Global usage in strategic industries

A material is classified as Strategic Raw Material, if global demand for the material is high and if it is used frequently in strategically important industries: digital, green, aerospace and defense.

- Critical Raw Materials: Economic importance and High Supply risk

A material is classified as Critical Raw Material, if it is frequently used across the overall EU economy, supply risk is high, and possibilities for substitution are low. Supply risk is determined by concentration of sources. Is a raw material exclusively mined in some few countries? The EU explicitly mentions in their document the dependency from China (97% of EU magnesium imports) and the concentration of cobalt in Democratic Republic of Congo (63% of total world extraction).

In total, the EU sums up a large list of different raw materials:

Strategic Raw Materials

|

Bismuth |

Manganese – battery grade |

|

Boron – metallurgy grade |

Natural Graphite – battery grade |

|

Cobalt |

Nickel – battery grade |

|

Copper |

Platinum group metals |

|

Gallium |

Rare earth elements for magnets |

|

Germanium |

Silicon metal |

|

Lithium – battery grade |

Titanium metal |

|

Magnesium metal |

Tungsten |

Critical Raw Materials

|

Antimony |

Helium |

|

Arsenic |

Heavy Rare Earth Elements |

|

Bauxite |

Light Rare Earth Elements |

|

Baryte |

Lithium |

|

Beryllium |

Magnesium |

|

Bismuth |

Manganese |

|

Boron |

Natural Graphite |

|

Cobalt |

Nickel-battery grade |

|

Coking Coal |

Niobium |

|

Copper |

Phosphate rock |

|

Feldspar |

Phosphorus |

|

Fluorspar |

Platinum Group Metals |

|

Gallium |

Scandium |

|

Germanium |

Silicon metal |

|

Hafnium |

Strontium |

Source: European Commission (2023b).

The list of Critical Raw Materials is nothing new. In in 2017 already, the European Commission had published a similar list of 27 CRM – (Sostaric et al. 2021). However, the introduction of Strategic Raw Materials as a new category is an expansion of policy so far.

Critical Raw Materials in BiH

It is not a few of those strategic and critical raw materials, which potential for mining in Bosnia and Herzegovina is already on the way to be explored. Geologists from different universities in the Western Balkan regions have already explored potentials for expansion of CRM mining in Bosnia and Herzegovina. They detected significant possibilities for Bauxite, Magnesite, and Antimony mining all over the country (Sostaric et al. 2021). More precisely, they listed the need for further geological investigation of (existing) deposits in the following regions:

- polymetallic antimony deposits in Čemernica and Podhrusanj

- antimony fields in Srebrenica and Rupice

- magnesite fields in Kladanj, Banja Luka, Teslic, Novi Seher

- Bauxite in Vlasenica, Srebrenica, Grmec Mountain in Una-Sana and between Posušje and Trebinje

Some deposits investigated are abandoned, others already operating or under development, others not yet explored. In any way, mining operations are considered not at maximum capacity and there is significant potential for upscaling of mining activities. Authors of the study even suggest that, once fully exploited, Bosnia and Herzegovina could become one of the main suppliers of Bauxite and Magnesite in Europe. The political economic consequences of such reliance on EU as well as the environmental and social effects of massive mining are neglected in such studies.

However, BiH is already the largest Bauxite producer among the Western Balkans Countries, (Giannakopoulou et al. 2021), and not much benefit is visible from it. Besides from Critical Raw Materials, there are precious metal deposits such as for ore and silver in the central region. Iron is already exploited at larger capacity. Still, again, what is stressed is Bosnia and Herzegovina’s potential for upscaling, targeting it as a yet underexploited resource hub. Researchers stress that a lot of mines for e.g. antimony, which is so far not produced, could be yet opened, which activates literally some explorer and gold-digging mentality (see Giannakopoulou et al. 2021, Sostaric et al. 2021).

EU Raw Material related initiatives in BiH

In fact, the EU is already on the way to explore potential resource deposits and puts its eyes on the Western Balkans. Even before the CRMA, the Czech Presidency pointed to the need to coordinate more strategic Raw Material reserves with the Western Balkans (Zachova 2022). Further, Western Balkan countries, among those Bosnia and Herzegovina, have been recently embedded into several newer EU strategic frameworks to serve as supplier for EU demand on raw materials.

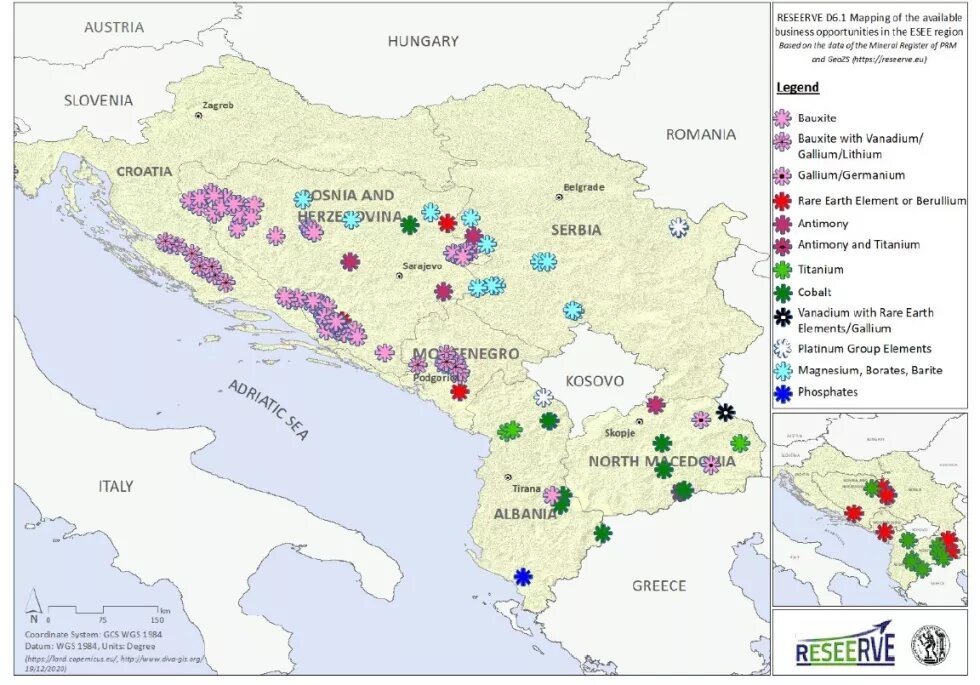

The EIT Raw Materials calls itself an innovation community founded in 2015 and co-funded by European Union. This platform already cooperates with 12 academic and non-academic research institutions in BiH. Among its activities in the region are an initiative for North Macedonia to promote mining investor-friendly legislation, while another initiative has a special focus on Bauxite deposits – which are in particular frequent in BiH. The Reseerve Project for mapping mineral Resources on the Western Balkans (EIT Raw Materials 2020) is a digital platform to update the so far fragmented geological data on raw materials. The Reseerve Project is supposed to explore the “Mineral Potential of the Eastern and South-Eastern Europe region”, and built up a Mineral register for the Western Balkan region (Reseerve 2023).

Reseerve is a reflection of how center-periphery relations, where the European peripheral countries would become main suppliers of materials for the green transition of the West, are gaining in weight again. The Balkans are mapped on their webpage as a mining pot. There is no information on potential environmental impacts on protected areas – but data on the exact geolocations and types of materials one can find there all over the country. The newly gained data allows future European Investors to set up projects which are in line with the CRM and might therefore receive benefits under the CRMA framework. Once classified as strategically important project, investors would benefit from easier access to finance and lighter bureaucracy, which would go hand in hand with softer regulations on human rights, labour exploitation, and environment.

BiH is also part of the European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA) – formed to facilitate raw material investments along all stages of the value chains, and funded by the European Union. Out of the former Yugoslav countries, only BiH, Slovenia, and Serbia have joined. In their latest Strategic Report, BiH, alongside with Serbia, is mentioned as mining Hub for Lithium. On the Serbian Side, controverse company Rio Tinto and EULIBOR are listed as mining companies, while on BiH side Arcore is listed on Lithium and Borates Mining. Additionaly, BiH is listed with Magnesium for Europe for Magnesium metals production (ERMA 2023).

Under the EU Horizon 2020 Project, active mining possibilities are explored on the field. While Serbia is already large scale included (8 projects), 4 projects have been developing under Horizon 2020 in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Hedberg 2020, HMS, 2018). One of them included the exploration of under-sea mining in Vares in lake Nula, which caused massive protest of the local population, among it, an open letter to the EU Delegation to stop the project. The method of under-sea mining which should be tested at lake Nula was completely new in research, it had only been tested beforehand in one lake in England – which was not a vivid lake with a natural ecosystem but the result of a larger waste deposit. The operator VAMOS declared on that it would “Conduct field trials with the prototype equipment in abandoned and inactive mine sites”, (Cordis EU), suggerating that there would be only limited environmental impacts on abandoned sites far-off. However, as their second trial spot, they chose a lake in the former mining town of Vares - a community not even in the EU, with their lake originating from clear springs and being rich in fish. The project could have lead to the depletion of the ecosystem of the lake – for the purposes of industrial development of the EU (Aarhus Centar u BiH, 2018).

Environmental and human rights failure

The CRMA has alarmed civil society organizations and environmental activists due to unbalanced power relations between communities and private investors, between suppliers and EU demanders, and circumvention of social and environmental protection measures as well as the local community. The narrative of the whole document is very much narrowed on securing the supply chain – democratic or socio-ecological principles are not important. CSOs have been raising serious concerns several times with letters and other public statements and demand fundamental changes in the document. SOMO states:

“The proposed strategy of the EU to secure access to CRMs and SRMs will not lead to a sustainable supply of minerals for Europe because it will exacerbate human rights and environmental risks and undermine development in partner countries. Critically, the CRMR fails to address Europe’s unsustainable consumption, and it reinforces an economic framework where resource-rich third countries are pushed to remain as suppliers of raw materials that feed the consumer demands and unsustainable lifestyles of global powers.” (Gonzalez 2023, p. 1)

The document shapes a framework which indeed does not foresee any limitation of Europe´s raw material footprint. Consumption and resource intensive production of goods are not foreseen to be limited anyhow, and the limited promises of upscaling domestic mining and recycling cannot cover up the fact that the EU industrial centers keep their excessive overconsumption mainly through imports of raw materials (CSO open letter 2023). While high value industrial production and consumption appears within the EU, the mining industries, with all its pollution and detrimental effects on health, social security, biodiversity and land depletion will at most stay outward – in EU neighboring states and the Global South. With respect to Lithium, the largest reserves in Europe are actually CSOs mark the failures of the document a matter of “global justice”, and appeal to the EU to end the exploitation of third countries for its own overconsumption (CSO Open Letter 2023). The document is therefore yet another acknowledgement that the EU will keep its “imperial mode of living” (Brand and Wissen 2017), at the expense of peripheral supplier countries and local communities. In fact, the largest Lithium reserves are found to be located in the very geographical center of Europe at the Czech-German border (En-former.com). They could meet the demand of the larger automotive industry in Germany. Other Lithium Resources on the Upper Rhine, which could be mined under water, are viewed skeptically by local communities for ecological reasons. Therefore, it is not sure if the German resources will be totally exploited, and even if so, Germany could only cover up to 19% of its lithium demand for battery cell production by domestic resources (Zimmermann 2023). Given that and similar cases across the EU, the EU will in any way seek for outer-EU sources. The EU would rather seek for new resource exploitation possibilities on the periphery than sacrificing their production and demand for resources. At the same time, outer-EU sources will be used to cushen risks on domestic extraction possibilities through local oppositionists within the EU.

Diego Marin from the European Environmental Bureau calls the CRMA “colonial greenwashing” (Simon 2023), as it does not address the global imbalances of power through sovereign debt, which then lead to excessive Raw Material exports. Raw Material Supplier Countries would have to sell their resources under low prices to serve foreign debt obligations of European and American Banks. He doubts that expansion of raw material export in the supplier countries – mostly in the Global South - is even in their interest. In fact, financing of mining projects by foreign financial institutions could lead to increased debt distress of supplier countries (Simon, 2023). Further, the EUs plans on building up stocks of minerals can cause stockpiling, which can distort market prices and make raw materials inaccessible for non-EU countries for their own green transition.

At the same time, by securing its exclusive access in third countries through Strategic Projects and Partnerships, the EU denies local communities autonomy over their local resources and the right to decide on their own on their development. While Civil Societies are not involved in the Governance Board of the CRMA, neither are they granted the possibilities and time needed to react on investment projects. CSOs claim that it cannot be that accelerating permission would be at the expense of local stakeholder participation and democratic principles. However, the fact that local community engagement is not required for permission, reveals the priority of Private Investors over the will of local communities and activists when it comes to EU strategic interests. Local communities, just on occasion settled on a potential CRM deposit, will be, once a foreign investor is interested, left alone in the battle to claim their right of local self-autonomy. CSOs appeal to the EU to respect the right of local communities to say no to mining projects on their territory.

As Strategic Mining projects are classified as of wider public interest, they are legally given the possibility to structurally overrule EU regulations on biodiversity, ground water and bird protection (Gonzalez 2023). Hence, the EU shapes a regulatory framework, where economic interests will have priority to environmental standards. While it could be argued, that those Strategic Projects constitute only exemptions from environmental regulations, the sheer number of hundreds of Critical Raw Materials and potential mining sites for them – even only all across Europe – reveals that the large-scale approval of Strategic Projects will lead to structural degradation of the environment over wider territories.

In fact, as the CRMA does not foresee wider environmental and social assessments in their certification processes, and Risk Monitoring is merely focused on supply risk than socio-ecological impacts, it gives much scope for mining investor companies to exploit low regulations in third-countries. If the EU does not oblige them to cope with sustainability and human rights, how should communities in countries with weak governments and human rights and environmental standards protect themselves from exploitation and pollution? Instead, international investors find beneficial conditions, where due to the power imbalance, they can negotiate cheap prices and exploit cheap labor under low-standard working conditions. Environmental standards do not need to be strictly followed or are not even put in place.

The same holds up for Bosnia and Herzegovina. BiH is one of the most biodiverse countries in Europe, with up to 30% of Balkan flora are located in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Rare metal mining expansion could threaten biodiversity. As European Union does not foresee a binding legislation for punishment in case of environmental damage, the responsibility for such measures is completely up to the country. However, in BiH, biodiversity protection is low. There is no monitoring, and there does not exist a legislative framework to enforce biodiversity protection on mining sites. Only 1,4% of its territory are considered protected, which is the lowest on the Western Balkans, and natural protection legislation is not yet aligned with EU standards (OECD 2023, EU Commission 2020). There would be no strong legal power balance to protect nature from biodiversity losses in mining. BiH could therefore become a cheap mining place where investors do not have to fear strong ecological regulatory measures and ecological considerations do not need to be strongly put into account. UNEP estimates that already, due to opencast mining or opencast exploitation of mineral ores, 15 000 ha of land in Bosnia and Herzegovina were have been damaged (UNEP, 2012).

Conclusion

The EU CRMA shows that there will be upscaling of extractivist activities in the future, and BiH is yet one of the dozens of countries which will come under the pressure of European Mining Investors and the rising number of future projects. Although still on the way to be passed by the European Parliament, the current draft of the CRMA shows that the EU will not automatically foresee high environmental and social standards in mining, but leave it up to the supplier countries and local communities to live with the consequences of a mining site next by. What stays for us is the possibility to react and think about our role in the process. Recent developments have already shown that more international companies will come to mine in BiH, and apparently, there is some political negotiations, on any subnational or national level to place BiH in the field of the European Raw Material Chain, but it is not yet visible what strategy is pursued right now and there might be scope for choosing the direction of this engagement.

Does BiH want to become a supplier country for the EU? And if so, under which conditions? Does the citizens of Bosnia and Hercegovina want the conditions to be solely reliant on EU legislatives, on the CRMA? Bosnia and Hercegovina should consider setting up own standards for social and environmental protection to avoid full-scale exploitation. It is the decision over becoming a sheer supplier of raw material, or gaining more access to their own resources and technology, processing more, making own products. Does Bosnia and Hercegovina want to dig-in, because the EU will dig somewhere anyways, or will the country leave their resources under the ground – for the future, for the sake of the environment and the health of the population?

Protests in Vares, with an open letter recently published to EU representatives, has shown that the public becomes aware of the detrimental effects of mining. There are protests here and there, but structural public awareness is needed and protesting actions on a wider scale. A wider public debate is needed, about autonomy over the development of the country, and if extractivism should be part of it or not – because if we do not debate, BiH will fall under the EU umbrella of raw material extraction – but under their conditions, under their influence, with their companies benefitting. The development of this process, the development of mining, of raw material export, and of the affection of the local communities, shall not fall out of the hands of the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Literature

- HMS (03/27/2018). PISMO EUROPLJANIMA IZ VAREŠA: Zaustavite testiranje! https://hms.ba/pismo-europljanima-iz-varesapismo-europljanima-iz-varesa-zaustavite-testiranje/ Last accessed 6/19/2023.

- Aarhus Centar BiH (04/07/2018). Razvoj evropske industrije na teret osiromašenog Vareša? http://aarhus.ba/sarajevo/en/1234-razvoj-evropske-industrije-na-teret-osiromasenog-varesa.html.

- Brand, Ulrich and Wissen, Markus (2017). The Imperial Mode of Living. Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism. Versobooks.

- Cordis EU. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/642477. . ¡Viable and Alternative Mine Operating System!. Last accessed 6/19/2023.

- EIT Raw Materials (2020). EIT RawMaterials Western Balkans Activities. Presentation, 09/09/2020.

- Enformer.com (2020). Riesige Lithium-Vorkommnisse im Erzgebirge vermutet. https://www.en-former.com/riesige-lithium-vorkommen-im-erzgebirge-vermutet/

- European Commission (2023a). Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL establishing a framework for ensuring a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials and amending Regulations (EU) 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/1020.

- European Commission (2023b). ANNEXES to the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for ensuring a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials and amending Regulations (EU) 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/1020.

- Giannakopoulou et al . (2021) Mineral Raw Materials’ Resource Efficiency in Selected ESEE Countries: Strengths and Challenges: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-4605/5/1/83#B12-materproc-05-00083

- González, Alejandro (2023). Ten reasons why the European Commission’s proposed Critical Raw Materials Regulation is not sustainable – and how to fix it. SOMO position paper.

- Hedberg, Jonas (2020). Horizon 2020 Raw Material Research & Innovation ERA-MIN 2 final conference. https://www.era-min.eu/sites/default/files/docs/horizon_2020raw_material_ri_mr._jonas_hedberg.pdf

- Menga, Marina (2023). The Critical Raw Materials Act: digging in the dirt for a sustainable future. Climate Foresight, 04/27/2023. https://www.climateforesight.eu/articles/digging-in-the-dirt-for-europes-green-future/

- OECD (2022). Multi-dimensional Analysis of Development in BiH. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/8e6d1ccd-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/8e6d1ccd-en#section-d1e34404

- Pegorin Fabio, Anderhuber Florian, Bounsaythip Catherine, Bureau Gildas, Chevillard Naomi, Della Rosa Francescantonio, Carlos Escudero, Barbara Forriere, Roland Gauß, Gautier Pierre-Alain, Gervais Estelle, Grivel Frederic, Lamm Laurence, Vanessa Lorenz, Renaut Mosdale, Patrick Nadoll, Olli Salmi, Fabrice Stassin, Alberto Tremolada, Massimo Gasparon (2023). Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion: A European Call for Action. A report by the Materials for Energy Storage and Conversion Cluster of the European Raw Materials Alliance. Berlin.

- Simon, Friedrich (2023). EU pushes alternative model to China in global race for raw materials. Euractiv.com, 05/31/2023. https://www.euractiv.com/section/circular-economy/news/eu-pushes-alternative-model-to-china-in-global-race-for-raw-materials/

- Šoštarić Sibila Borojević, Markelj Anže, Jašarević Eldar and Haindl, Angelika (2022). The geological potential of antimony, bauxite, fluorite, and magnesite of the Central Dinarides (Bosnia and Herzegovina): an exploration and exploitation perspective. Journal of the Croatian Geological Survey and the Croatian Geological Society (75/2). pp 269–287.

- UNEP (2012), State of the Environment Report of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2012, United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/9437/-State_of_the_Environment_Report_for_Bosnia_and_Herzegovina-2012SoEReport_BosniaandHerzego.pdf?sequence=3&%3BisAllowed=.

- Wouters, L. (2023). Key players: Why mining is central to the EU’s critical raw materials ambitions in Africa. ECFR.eu, 03/24/2023. https://ecfr.eu/article/key-players-why-mining-is-central-to-the-eus-critical-raw-materials-ambitions-in-africa/

- Zachova, A. (2022). EU should establish reserves of key raw materials, says Czech presidency. Euractiv, 09/14/2022. https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/eu-should-establish-reserves-of-key-raw-materials-says-czech-presidency/

- Zimmermann, A. (2023). Tremor fears lay down hurdles for Germany’s lithium mining plans. https://www.politico.eu/article/germanys-lithium-extraction-earthquake-mining/

- (09/28/2020). CSO Open Letter to Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič and Commissioners Thierry Breton and Virginijus Sinkevičius. Re: Civil society concerns on EU critical raw materials plans.