Moving out

The state of mass emigration from Bosnia and Herzegovina and its implications

To plan a trip from Sanski Most to Germany by bus, one would need to book a ticket well in advance and could expect it to be packed with adults and children. More likely than for a short holiday, people make the journey to attend job interviews, and to move there permanently. Lately, a common saying in the local community is that there are more people from Sanski Most living in Munich than in Sanski Most.

The Union for Sustainable Return and Integration in BiH estimates that around 80 000 Bosnian citizens have emigrated since 2013. This is based on both legal and illegal departures. The Union found that it is not solely individuals who move abroad, but that whole families are leaving their communities. Among the municipalities with the most departures are Sanski Most, Zvornik, Bijeljina, and Brcko. In the last two years, for example, the Union reports that 2300 families have left Sanski Most.[1]

Data from the World Economic Forum[2] supports vast emigration claims. Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the countries least able to retain talent for its workforce, with most skilled/educated people seeking opportunities abroad. Out of the 140 countries analysed, it ranks among the last, at number 136, only outperforming Moldova, Myanmar, Venezuela and Serbia.

Relaxed visa rules

Official figures show that the number of Bosnian migrants to Germany has been rapidly increasing in the last three years. Whereas before 2013 the numbers were more constant, Germany’s Bosnian population increased by more than 15 000 between 2013 and 2015.[3] These numbers will continue to increase; as of the 1st of January 2016, Germany has relaxed rules for Bosnians seeking employment in the country by making it easier to secure a work visa. Perhaps not coincidentally, 2016 marks the year that the German Embassy in Sarajevo has reached one of the highest numbers of visa applications in the world. Considering the fact that BiH is a small country, with only 3.8 million residents, it represents an extremely large volume of applications. The embassy has reported that it has 50 appointments for work visas every day, each booked 14 weeks in advance. Young people from Bosnia and Herzegovina can also apply to undertake vocational training in Germany, which allows them to legally work at the same time as they earn a qualification. This opens doors to more people, as university is not the sole option to gain relevant skills for a visa.

Emigration is further facilitated by Croatia’s accession to the EU in July 2013, as many Bosnian Croats, the majority from Herzegovina, hold Croatian passports, and therefore have access to joining the EU labour market.

High youth unemployment rates

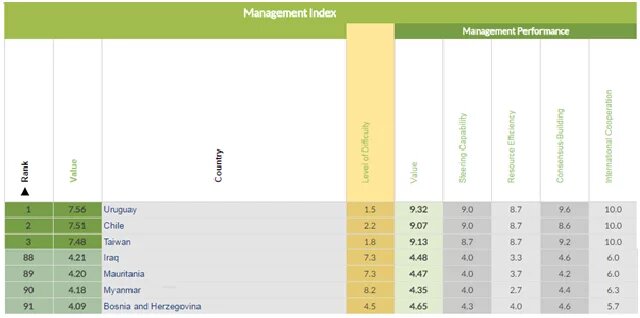

The reasons for this wave of emigration will perhaps fail to surprise people from BiH or those familiar with the country’s affairs. Ask anyone in Sanski Most why people are leaving, and the simple explanation will include politics, economics, and life (or the lack of conditions for life; ‘nema zivota’). Emigration trends reflect the lack of opportunities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and economic and social reforms which bear a legacy of failure. In March 2016, the unemployment rate in BiH was 42.36%, whilst the youth unemployment rate was much higher, at 50%[4]. The 2016 BTI report[5] ranks BiH’s political management at 91 out of 129 countries observed, meaning the current government is dealing poorly with the country’s transition to democracy and a functioning market economy. At the global level, BiH performs worse than countries in the Western Balkan region, such as Kosovo, Albania, Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro, but better than some Gulf states (Saudi Arabia, Oman), former Soviet Union states (Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan), and several states from the African continent (Sudan, Somalia, Chad). The absence of progressive reforms and the bad ranking in the political management index is in part due to a lack of consensus within Bosnia’s institutional structures. In the current power sharing agreement, it is common that as one party pushes forward a reform, another vetoes it.

There is a visible lack of political will in Bosnia, and it occasionally still takes international intervention to initiate change processes. For example, it took an initiative from the British and German governments to move the Bosnian government from a state of stagnation, having repeatedly failed to agree on and to implement key terms required in the EU integration process. This included finding a compromise on some required reforms; notably, the implementation of the Sejdic and Finci vs BiH judgement, which would have abolished the institutional discrimination of minorities running for government office. The compromises, and push forward with the EU integration process, however, rested on the renewed promise of creating reforms. So far, these promises are yet to be fulfilled. In a recent interview, Christian Hellbach, German Ambassador to BiH, expressed his criticism and disappointment with the Bosnian political elite, regretting the fact that they put their nationalistic interests above those of their citizens, who want to see progress and reforms. The political deadlock which results from ethnic-based party interests, poses a major barrier to finalising agreements, which means reforms don’t get passed and seem to constantly be delayed. One solid example of this is one of the main requirements for BiH to achieve candidate status: a coordination mechanism, which seeks to ensure that the country as a whole can negotiate with EU. The governing parties of BiH, are yet to agree on this basic mechanism.[6] The ambassador further stated that by institutionalising nationalism instead of fighting it, BiH’s political elite have nothing of real importance to give to their own people. This current state of affairs only deepens the social and economic crisis.

Corruption in the employment sector

Last but not least, nepotism and endemic corruption practices best serve the interests of the current status quo, and push those outside of these networks to leave. One individual from Sanski Most clearly stated that they do not plan on returning to Bosnia and Herzegovina after having recently emigrated, as corruption ‘is taking over’ and they do not see a future for themselves in the current system. The local Transparency International (TI) office in BiH showed that this opinion is shared by Bosnians at a much larger scale. Citizens here consider corruption as one of the main problems in BiH, with a strong emphasis on corruption in the employment sector. Overall, corruption in employment in the public sector accounts for more than half of the official reports. [7] The latest Corruption Perception Index from TI (2015) also shows that corruption is well known of here. Bosnia scored a mere 38 points on the scale of 0-very corrupt to 100-very clean, only ranking better than Kosovo in the Western Balkans. [8]

Bosnia’s brain drain and high emigration trends will not only affect its internal labour market, but will also have a negative impact on demographics and future political change. It is predicted that by 2030, BiH’s population will shrink by 5% due to a combination of factors, including negative net migration.[9] Jasminka Džumhur, Ombudsman for Human Rights in BiH, recently quoted[10] a Red Cross study which reveals that in 35 years, Bosnia’s population will be the oldest in the Balkans. Statistics are but a number, however, if the young leave, and the trend is not reversed, Bosnia could be left with the enormous task of supporting a population with an even smaller, tax playing labour force, and a large number of old, retired citizens. Such outcomes for states are unsustainable, and governments in Europe, particularly in Scandinavia, are already trying to reverse these trends.[11] The German Ambassador to BiH is also of the opinion that the current migration trends, especially concerning young people, could lead to a demographic disaster. Moving towards a more productive governance system, which will seek to secure a better future for the country, requires great political change, but who will lead this? In Sanski Most, a good number of people intending to leave are often employed, skilled, and have relative economic security, so their motivation to leave is further influenced by political factors, such as instability, corruption, lack of progress, and disillusionment with the state of democracy in Bosnia. The chance of much needed change diminishes when people who have an alternative vision for BiH’s future leave the country, whilst people comfortable with and privileged by the status quo remain, isolating the increasingly small minority of politically progressive Bosnians.