Set against the background of the coronavirus pandemic and an impending economic crisis, the Croatian parliamentary election held on 5 July 2020 promised to be a very tight race. Pre-election polls signalled a neck-to-neck contest between the two mainstream parties, and the ‘threat’ posed by a newly-formed far-right coalition that looked set to become kingmaker. Both forecasts proved to be untrue.

The ruling conservative party HDZ - led by Andrej Plenković, a former MEP and a representative of the party’s moderate faction - easily re-established its dominance over the political scene of the country. However, the election outcome is not necessarily “more of the same”. Significant novelties have appeared on both sides of the spectrum. This brief gives an overview of the main political actors and of the way the campaign played out, before passing on to discuss the emergence of Croatia’s first-ever sizeable green force in parliament: Možemo.

An unusual campaign: ebbs and flows in coronavirus times

The vote was called early by a few months: although 2020 was already set to be an election year in Croatia, the fear of a second wave of the pandemic in the autumn provided the official reason for this rescheduling. It is however apparent that the timing was also supposed to suit the ruling party, the right-wing Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ). Its leader, Andrej Planković, wanted to capitalise on the good handling of the coronavirus crisis at the beginning of the pandemic: cases were kept very low and the daily increase hit zero in late April-May. By this time, the support of the population for the direction the country was going towards had sharply risen from just above 20% to over 50% (Nova TV, 24 April 2020; Cro Demoskop).

However, after this peak of optimism, the reopening of the country in June brought an increase in coronavirus cases (Croatia’s overreliance on tourism, which constitutes up to 20% of GDP, underpinned the need to let travellers in for the summer season). But with coronavirus cases going up, the confidence in the institutions, as well as the support for the ruling party, fell in the polls. Furthermore, the organisation of a tennis tournament in Zadar in the frame of the Adria Tour by world n.1 Novak Đoković ended with a PR backlash: tennis players Nikola Dimitrov, Borna Ćorić, and Đoković himself, resulted positive to Covid19, and the final of the tournament was called off (TheWeek, 23 June 2020).

Other elements complicating a campaign that was initially supposed to be smooth sailing for the HDZ included the ‘Wind Park’ corruption scandal (Euractiv 2020), implicating former Knin mayor and HDZ member Josipa Rimac. This exposed, once again, the deep issues of clientelism and grand corruption that have characterised the HDZ’s rule in Croatia over the past three decades (Čepo 2020). All these factors contributed to a scene-setter seeing a tight race between the HDZ and its main contender on the left, the socialist democrat party SDP.

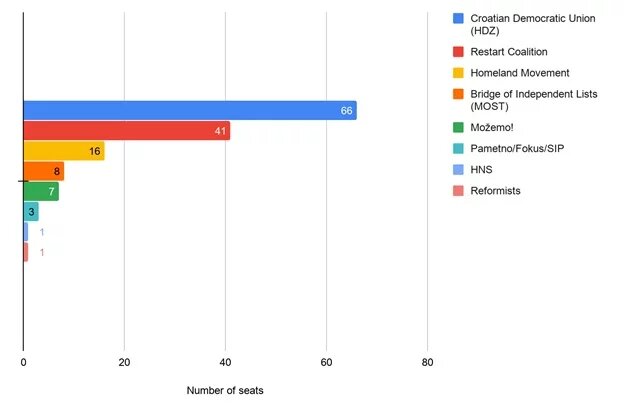

The reasons why the touted political boomerang turned into an open-goal free kick for the HDZ, which obtained 66 seats in parliament and was able to quickly form a government with the support of the representatives of the ethnic minorities and two minor parties, should be seen in the context of two sets of factors: structural and contingent. Structurally, the HDZ enjoys the most loyal electorate in Croatia, along with a very strong clientelistic base (Biočina 2019; Čepo 2020). Furthermore, the three seats reserved for out-of-country voters have, so far, always gone with the HDZ (State Electoral Commission), whose appeal among the Croat population of Herzegovina is particularly strong.

Specific to this election, the very low turnout (49.6%) - compounded by coronavirus-related anxiety - favoured the party with a better ability to get people to the polls. Last but not least, the agency of the HDZ leader and prime minister Andrej Plenković in securing this strong result for his party is undeniable. Starting from the figure of a grey Eurocrat who took over the premiership in 2016 after a string of corruption scandals, and unpalatable far-right rhetoric, characterising his party, Plenković grew into a skilful politician who managed to dispose of his enemies in either seamless or less elegant ways. His standing in the European Union is strong, as the controversial EPP pre-election message in support of the HDZ, issued by a series of prominent figures including Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, shows (Morgan 2020). Many Croatians who are not HDZ sympathisers would privately acknowledge that they saw Plenković as PM, while they did not see the leader of the centre-left, Davor Bernardić, covering this post.

The low popularity of the leader of the Social Democrats (SDP) was thus the first of the troubles affecting this party, but not the last. SDP voters are aging, as are their policies: the party approached the 2020 elections with pretty much the same economic programme used for the 2016 parliamentary elections. The disproportional representation of men in the top cadres, to the detriment of excellent women, is another major issue. The party also suffers from democratic deficit: when Bernardić took power, he sanctioned all those members who dared criticise him. The end result is the alienation of the younger and more progressive voters, which led to the staggering result of only 41 seats for the centre-left Restart coalition (of which mere 32 went to the SDP, while the remaining 9 seats were won by their coalition partners).

On the far-right side of the spectrum, the 16 parliamentary seats gained by the Homeland Movement (Domovinski Pokret), led by former folk singer Miroslav Škoro, have not been met with tears of joy. Although the result is indeed spectacular for a newly formed party, this formation had hoped to play the role of kingmakers in the new government, but the landslide victory achieved by the HDZ and the subsequent coalition with two minor centrist parties have neutralised all of their negotiation power. Their goal was ultimately to take over the HDZ and bring it further to the right, where they think the party belongs.

The outcome of the election avoided this ‘Orbanisation’ of Croatia, as some commentators had feared (Euronews 2020). Aside from their ideological stances, which are also distinctly anti-Serb, evidence is mounting that the interests of many Homeland Movement members are much more prosaic: the grouping has been dubbed the ‘Property Movement’ (Imovinski Pokret) due to the corruption scandals that have accompanied some of their members. The funding originating from a Gazprom-connected company in Croatia, which had in the past donated funds to the HDZ, reinforced this image (Klancir 2020; Vidov 2020). It will be interesting to see how many of the MPs elected under this umbrella will end up defecting back to the HDZ.

A conservative reformist party that supported Miroslav Škoro at his presidential election run in December last year, Most (Bridge of Independent Lists), got hold of 8 seats. After backing a HDZ-led government twice, in January and October 2016, and after both experiences had ended bitterly, the party promised not to work with the HDZ again. Lots of dust was raised by their ideological stances and in particular by their outspoken opposition to abortion, even in the case of rape (as stated by Most’s Nino Raspudić).

The Croatian Sabor will also host, for the first time, a grouping of three centrist parties: Stranka Sa Imenom i Prezimenom (SSID), Pametno, and Fokus, who promised to play the role of a constructive, but intransigent, opposition. But the real surprise of the election was on the left-side of the spectrum, with the excellent result achieved by the left-green coalition led by Možemo (We Can). At their first national electoral race, and in contrast to the 2 or 3 seats indicated by pre-electoral polls, they ended up scooping 7 mandates.

The Green Wave reaches Croatia

Možemo’s story started on the streets. Most of the actors who have gathered around this coalition honed their arguments and built their stamina through years (in some cases, decades) of political engagement in movements fighting for women’s rights, green policies, social equality, a more accessible and fairer education, workers’ rights, and against corruption. The strong result achieved by the Zagreb is Ours (Zagreb Je Naš) movement at the 2017 local elections in Zagreb spearheaded the political activity of what was to become Možemo. On that occasion, activists promised that “this [was] just the start”, adding that “the SDP has given up on values such as social equality, the widening of democracy, environmental sustainability and gender equality and can no longer speak about the challenges of the modern left. We are this new political power” (Zagreb je Naš 2017; Faktograf 2017).

They were true to their promise. By entering the city council, they kept the until then uncontrasted ‘sultan’ of the city of Zagreb, mayor Milan Bandić, on his toes, putting under a magnifying glass the many corruption affairs the mayor is accused of. At the 2020 parliamentary election, Milan Bandić’s party failed to pass the threshold. Many are now waiting with bated breath for the Zagreb local elections in 2021, when, it is touted, this group of activists-turned-politicians could bring down Bandić from the post he has been covering for the past two decades.

The significance of Možemo’s achievement goes beyond Croatia, galvanising similar movements and political parties in the wider region. In Montenegro, the movement URA – already a member of the European Greens – congratulated them immediately after the elections (URA / Twitter). In Serbia, the group has a long-standing collaboration with the activists from Let’s Not Drown Belgrade (Ne Davimo Beograd), which is connected to organisations throughout Serbia under the umbrella provided by the Civic Front (Građanski Front). While it is important to keep in mind the specific political situation in each country, Možemo’s example shows that activists can make a real difference in a more formalised political environment. The energy and feistiness of their vision is summarised by their campaign song, by musician Mile Kekin: “Let’s exit the roundabout, the battle will be fierce / I dreamed that everyone was waking up and, around me, I saw happy people” (Kekin / Youtube 2020).